Move people with your vision

When Bill Shankly took over as manager of Liverpool Football Club, they were a second-rate side, languishing in the old Second Division.

By the time he left in 1974, they’d won three First Division titles, one Second Division title, two FA Cups and one UEFA Cup.

Unrecognisable from the deadbeat side he’d taken charge of in December 1959 – even down to their kit.

Because when Bill Shankly took over as manager of Liverpool, they didn’t play in their iconic all-red strip.

They played in white shorts and white socks, with white piping on their red jerseys.

But Bill had an idea.

Impressed by Real Madrid’s all-white kit, and using his gut instinct for colour psychology, he made a switch so powerful that it’s hard to believe it hasn’t always been that way.

One day, after training, Bill bounded into the players’ dressing room.

He threw a pair of vivid red shorts to one of his players.

“Get into those shorts and let’s see how you look,” instructed Bill.

Because he had a theory: red is for danger; red is for power.

And he didn’t just choose any player to model this new kit, he chose his captain, Ron Yeats.

The 6ft 2in fellow Scot he’d signed from Dundee United, a part-time slaughterman who was as strong as an ox and twice as wide.

The bemused centre-half duly obliged and donned the red shorts, with the addition of red socks.

As he walked down the steps towards the players’ tunnel, he could see his manager, and assistant Bob Paisley, in the middle of the pitch.

And as Yeats approached them, all in red, Bill exclaimed: “Christ, Ronnie, you look awesome, terrifying; you look seven feet tall!”

His stocky presence was made all the more imposing by the all-red uniform.

A move intended to strike fear and intimidation into the hearts of opponents.

Bill was happy.

And on the 25 November 1964, the man-mountain from the “Granite City” of Aberdeen, led out his teammates against Anderlecht in the first round of the European Cup.

All in red for the first time.

The art of theatre was not lost on Bill: he instructed Yeats to stand in the centre circle of the Anfield pitch.

“Walk around him,” urged Bill, as he invited a group of journalists to behold his rough-hewn granite obelisk.

Splendorous in scarlet.

The match was played at a cracking tempo.

Yeats the rock: a huge, defiant red-jasper sentinel in the middle of the defence.

Hunt, St John and Yeats on the score sheet: the captain’s forceful header, the skipper’s first at Anfield.

They shattered the pride of Belgium: 3–0.

And Bill knew that a red glow had been ignited at Anfield that night: one that burned fiercely for more than 20 years.

He knew the importance of getting people to sit up and take notice.

His symbolic move captured their supporters’ imagination, and that of the onlooking press too.

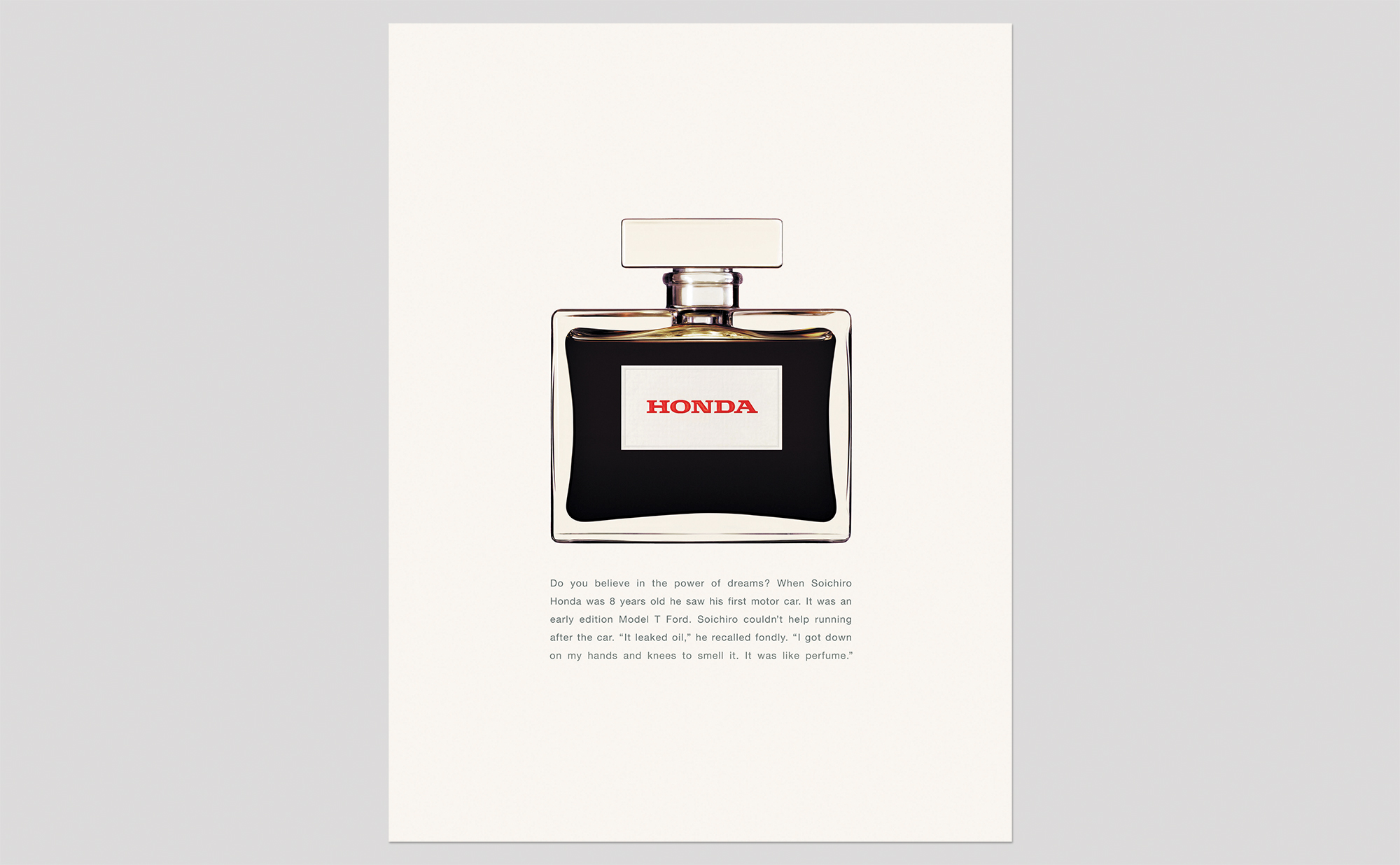

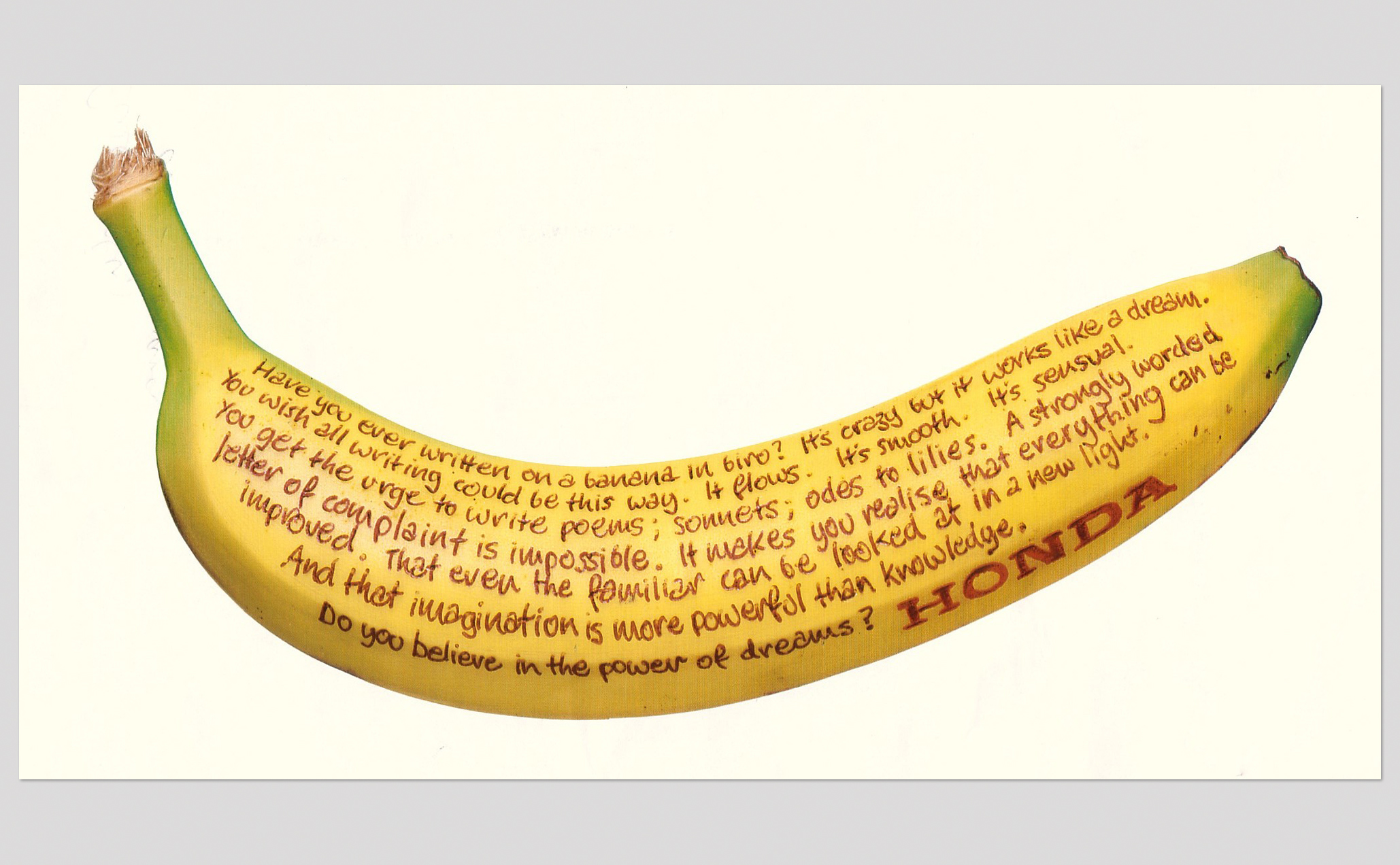

Projecting a very clear sense of who or what you are, and the purpose of what you are doing, is critical to success.

Connecting as much, if not more, on an emotional level as on a rational one.

Through the symbol of reevaluation: a red kit, Bill projected a powerful identity, not just a superficial image.

Bill was sending out a visual message to reinforce the changes he’d made to LFC’s training ground, training methods, footballing philosophy and ambition.

A move intended to amplify these changes.

And, in doing so, intimidate the opposition, inspire the press, captivate the fans and motivate the players.

He’d brought his vision to life so people could see it, understand it and get behind it.

And like Bill, we turn breakthrough thinking into real-world outputs that fuel action and drive change.

— DB