POV*: A purpose or essence won't build a brand. Telling a good story will

First brands were told they needed a pyramid, onion or key. Now it’s all about having a purpose, big idea or finding your “why”. Tomorrow it will be something else. There’s often a belief that defining a brand positioning in the right way is the key - pardon the pun - to success. It isn’t. There is no magic construct. The way you implement a positioning is far more important.

Command and control is dead. Build brands democratically.

In 1988, 44% of shoppers in the United States didn’t know who George Bush Senior was - and those who did knew only three things: (1) he was good-looking, (2) he was from Texas, (3) he was vice president. Later that year Bush Snr was elected president.

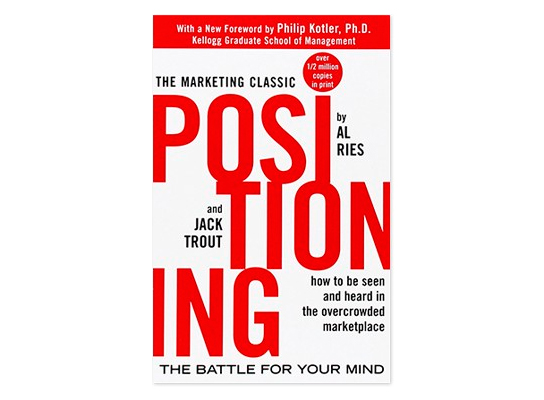

This example was cited by Al Ries and Jack Trout in their seminal book Positioning: The Battle For Your Mind. It was this text that first introduced the idea of positioning. The example of George Bush was used to support their fundamental premise. We live in an over-communicated society with excessive choice, so to cope with complexity people have learnt to simplify their decisions. Success in this world requires brands to find a simple message and own a distinct space in people’s minds.

Avis is the example cited by Ries and Trout. At the time, Hertz was the market leader. It was the best known car-hire company and therefore the default choice for most people. For 13 years in a row Avis lost money. Then they started running advertising with the message “we’re number two, so we try harder”. In each of the next three years their profits doubled and they were sold. Avis succeeded because they found a simple message that reframed the way people thought about choosing a car-hire company.

The world has changed since this campaign. We still live in a world of over-communication and excessive choice, but the media landscape is unrecognisable. We take in more than four times as much information every day as we did in 1986 - the equivalent of 174 newspapers. In the 80s you could craft your message and then reach millions of people using a handful of activity, be that a TV spot during Coronation Street or a newspaper ad. Brands operated like dictatorships: they were built through command and control.

The huge changes in media have had major implications for the way we build brands. The volume of communications activity that contributes towards a brand’s image is huge. The frequency is intense. Yet each piece of activity itself often has a much smaller audience. Huge teams of marketeers are required to deploy all of this. And because of their power to share or not, the audience is more central to success than ever before.

This view is supported by other leading thinkers and writers. Adam Sweeney of London Strategy Unit, talks about brands as the product of microinteractions:

“Brands as ubiquitous as Amazon, Nike and Starbucks Coffee have realised that every tiny moment that a user wants something - whether it’s to log in, to go for a jog, to relax - is a moment to assist, impress and even delight them in giving them something they want, when they want it. In ‘loyalty’, they aim for reinteraction - not repurchase. You don’t need just one monster insight or killer proposition: you need multiple microinsights about the fleeting wants and needs of a user as they arise (and they arise second by second).”

Adam Sweeney

John Grant, co-founder of St Luke’s, compares modern brands to molecules. They are built of successive and connected ideas, each of which adds to a brands interest and keeps it alive in people’s minds. He argues that Nike is not about a single idea of “winning” or “victory”, as many people claim. Instead, it’s the product of the cultural ideas that Nike has created, eg Run London and Nike Free.

The upshot is that past positioning techniques are no longer fit for purpose. Positioning is ultimately a brand management technique. A tool for controlling reputation. A single, rigid message won’t work today. Brands need to deploy more messages, more often, through more channels and teams. Modern positioning tools must allow brands to be built through grass-roots activism, not command and control.

Brands need narratives not onions

A brand needs a positioning in order to be coherent. Whether you see an ad, speak to a sales person, or visit a store, strong brands deliver a level of consistency. This isn’t about total uniformity. Much like people, brands can behave differently, dress differently and talk differently depending on the context. But brands must always feel like the same person.

This is where many brand management tools fail. Corporate mission and vision statements are frequently so generic, bland and unfocused that it’s impossible to see the vision. The same issue exists with brand onions, keys and pyramids. Anyone who has ever tried to brief a creative team using one of these will know the problem. They’re frequently so vague that it’s impossible to grab hold of a direction. Therefore they fail in their primary purpose.

Many thought leaders in this area have started to talk about other constructs for defining brands. david hieatt talks about having a purpose. Collyn Ahartfavours pursuit. In his acclaimed TED Talk, Simon Sinek advocates finding your why. John Grant defines 32 types of brand idea. Along a similar line,Robert Jones talks of the big idea. While Margaret Mark and Carol Pearson offer a range of brand archetypes.

So which is best? At one time or another, each of them has unlocked someone’s positioning. The problem with all of these - and the onions, pyramids and keys that came before them - is they suggest that successful positioning is about the construct. The truth is, there is no magic formula.

When you hear Ben and Jerry’s defined as “joy for the belly and soul”, or Disney as the “magic of childhood”, it’s easy to believe that these phrases are their secret. They’re not.

Few great brands have started out with such succinct definitions. Instead they develop over time. Many of these phrases only make sense looking back. These brands have such well-honed images that the phrases make complete sense. Without an established image, which is the case for a lot of brands embarking on this journey, these phrases wouldn’t make nearly as much sense.

At Squad we advocate positioning brands through a looser definition - what we call a central narrative. The brand will be built by a huge cast of agencies, partners, marketeers and customers. They’ll communicate through film, the written word and live performance. Each will add their own interpretation and style. What they need is a central plot. Think of it like fan fiction. Stories like Harry Potter and Star Trek have huge communities of fans creating their own stories. But it’s all based around a narrative and set of characters defined by the original author.

I’ve worked with numerous brands where articulating their narrative has worked extremely well. Take The Macallan, a premium Scotch whisky. Theirs is a story about preciousness. From the scarcity of the raw ingredients to the selectiveness of the distillation process, preciousness runs through everything they do.

ACCA are behind the world’s largest professional accountancy qualification. Theirs is a story about more paths to success. They offer the widest breadth of entry routes, modules and job roles. So wherever an individual wants to start from, and go to, they have the path that will get them there.

Defining your story can be immensely powerful. When we helped Wythenshawe Amateurs articulate their story of a homeless football club seeking a ground, it captured the hearts and minds of the media and celebrities. They even made it on to the ITV Evening News.

Successful political campaigns too will often have a central narrative than runs through every piece of communication. Think of New Labour - no more left or right: just centre - or Barack Obama: change.

There’s no magic process for finding a brand story. Much like a good author or journalist, it’s about having a nose for a story. Relentlessly explore and question everything. Use some of the positioning constructs identified earlier to think about the brand in different ways. When you find it you’ll know - like a good book or film, it will stick in your head. And rest assured, I’ve yet to find a brand without a good story somewhere.

Don’t let brand jargon ruin a great story.

Not long ago I went to buy a car from Volkswagon. The dealership was a tip: messy and dirty. I loitered for an age before the sales people paid me any attention. When they did, their attitude was awful. And not once was I offered a drink. Then I glanced into their staff room. On the wall I noticed a poster. It was titled “Our Purpose”. It read: “To offer the best customer experience for the best car brands in the world”.

Brands today are more dependent than ever before on their people. From what employees say on social media, to the attitude of call-centre staff and the service delivered in-store: all of these are more important than ever to the success of brands. A positioning is worthless if it doesn’t translate into experience. Brands that aren’t true to the image they promote will quickly be ousted - most likely on social media.

Once the positioning has been defined, embedding it within the organisation is crucial. It’s not enough for a small group of brand managers to get it. Everyone needs to get it. They must understand what it means for them and what is required of them. More than this, it must motivate them to want to deliver it.

When trying to embed a brand positioning, talking like a brand person can hinder not help. Many successful brands don’t talk about brand. Howard Schultz, the founder of Starbucks Coffee, once said that he didn’t set out to create a great brand - he set out to build a great company and the brand developed.

Another example is one of our client’s: Tebay Services. Renowned in the UK for being as close as a motorway service area comes to Harrods’ food hall. Over 40 years they’ve built an incredibly strong brand, yet for much of this time the company was run by John Dunning, a Cumbrian hill farmer. Not a classic brand background.

Although they’re not using the language of brand, both of these organisations have that crucial component of building a strong brand - a great narrative. They’ve found success because they’ve told these stories in an honest, authentic and believable way. There’s no mention of a brand essence or promise. Perhaps if Volkswagon had used a bit less brand lingo they’d have engaged people more.

Eric Ransdell of Fast Company tells the story of Nike. The global sportswear brand employs a number of senior executives who serve as corporate storytellers. They tell the story of how Nike’s co-founder, Bill Bowerman, decided that his team needed better running shoes, so poured rubber into the family waffle iron and created Nike’s famous waffle sole. New tech reps are taken to the field track (where Bowerman coached) and to visit the site where another athlete who inspired the creation of Nike’s first shoes, Steve Prefontaine, died in car crash. Dennis Reeder, a Nike storyteller, says:

“Every company has a history. But we have a little bit more than a history. We have a heritage, something that’s still relevant today. If we connect people to that, chances are that they won’t view Nike as just another place to work.”

Corporate storytelling on the scale of Nike doesn’t come cheap. A more practical starting point is creating a video to bring to life the brand story or manifesto. When we started working with Tebay Services, we cobbled together a short video in iMovie one Sunday afternoon. It was quick and cheap, but it had emotion - when we played it to the client, they cried.

This video has since been shot properly and is used to communicate the brand’s story to staff. Creating a manifesto is another great way to capture the brand’s story (phil teer and Patrick Morrison include some examples on their website: themanifestoproject.co.uk).

These are just some examples of how brands embed their stories within the organisation. There are many more ways of doing it. Whatever approach you take, keep it real - don’t let brand jargon get in the way of a great story.

- RG

Further reading

• Baked In, Alex Bogusky & Winsor

• The Big Idea, Robert Jones

• The Brand Innovation Manifesto, John Grant

• Do Story, Bobette Buster (The Do Book Company)

• Eating The Big Fish, Adam Morgan

• The Hero And The Outlaw, Mark & Pearson

• Positioning, Ries & Trout

• Primal Branding, Patrick Hanlon